This is the third in a series of posts about images of refugees. For the first post, click here. For the second, click here.

Photographs of refugees on land often work to make both the refugees themselves and the landscapes they’re walking on interchangeable—so many huddled figures trudging across so many featureless bits of countryside. My last post explored some of the reasons for this: they’re partly to do with the choices that picture editors make, and partly to do with the standard formats of newspapers or news magazines and the cameras, lenses, and film that were typically used to take the photos that appeared in them. (Only rarely do refugees’ own views or choices come into it.) And in the post before that I wrote, more briefly, about the typical news photograph of a group of refugees in flight, burdened with their possessions. The aesthetic roots of that very standardized image go back much further than mid twentieth-century: I traced them back to 19th-century narrative painting, and earlier standard subjects in the European Christian tradition of painting.

But what about the other standard image of refugees, which has been just as common on news websites recently as the ‘overland trudge’—that is, the image of refugees at sea?

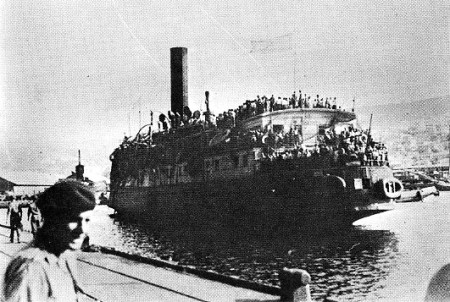

This picture shows the Albanian ship Vlora, in 1991. A cargo vessel that had recently returned to Albania from Cuba laden with sugar, the Vlora found itself heading to the Italian port of Bari with many thousands of Albanians aboard, hoping to escape the chaos of the end of communist rule. You can read about it on Migrants at sea, or watch this two-minute film on YouTube, and there’s a longer a documentary about the incident, too. The story doesn’t reflect especially well on the Italian authorities.

It wasn’t as an image from 1991, though, that the picture recently went double-viral. (I read about it here.) On the one hand, it did the rounds of Twitter racists amid claims that it showed thousands of ‘migrants’ in Libya or Syria preparing to invade Europe today. On the other, in black and white, it was circulated by anti-racists on Twitter—and Tumblr—claiming that the people in it were Europeans fleeing to North Africa during the second world war.

Like the Robert Capa photo I discussed in the last post, which appears on the cover of a history book about refugees in France (and on the internet as a picture of refugees in the Spanish civil war) even though it was taken in Israel just after independence, this photo shows us that refugees are interchangeable. You can pretend that a picture of people fleeing the political uncertainty and economic misery of Albania a quarter of a century ago shows Tripoli or Tartus this summer, and some people will believe you (and retweet). Or you can put the same picture in black and white and claim it shows European refugees in the 1940s, and other people will believe you (and repost). One of those claims is intended to provoke hostility toward refugees, and the other is intended to elicit sympathy—but it’s striking that both of them reduce the refugees themselves to silence in precisely the same way. The refugees become ‘speechless emissaries’, to borrow a term from the anthropologist Liisa Malkki.* In one claim, they bear mute witness to the threat of further swarms overrunning Europe; in another, they silently represent the shared human need, and right, to flee from danger. But they never get to speak for themselves. (It’s probably fair to guess that in neither case are the people behind the claim refugees.)

One of the reasons why a single image can be used in these different ways is because the ‘refugee boat’, just like the ‘overland trudge’, is already so well-established as a visual trope. The Vlora of 1991 can stand in for boats in 2015 or 1939 because we’ve already seen refugee boats in 2015 or 1939, and every decade in between. Look:

Let me restate something I wrote about images of refugees on land. The limitations of cameras, lenses, and film, the constraints of publication format, and the aesthetic (and moral) choices of photographers and picture editors all work together to mean that when you see a group of refugees in a photograph, you usually can’t see many identifying features of the landscape they’re walking across. This is even more true for images of refugees at sea: a patch of sea has even fewer identifying features than a patch of desert or hillside–if it is marked by distinctive shapes or colours, they’re changing all the time. The photos above were taken in the Andaman Sea in 2015, Hong Kong harbour in the late 1970s, Haifa in 1947, and (I think) Southampton in 1937. A dockside, if you can see one, doesn’t help much: a quick switch from colour to black and white was all it took to put the Vlora back in the same period as the Exodus 1947, carrying Holocaust survivors to Palestine, or the SS Habana, bringing Basque refugees to Britain in 1937.

When the boat is small and photographed fairly close up, you can make out some distinguishing features of the refugees, but not many: see what a difference the slightly more distant perspective in the first photo makes, compared with the second. Among the Rohingya refugees from Burma (2015) you can make out individuals, and tell adults from children; among the Vietnamese boat people in Hong Kong (1970s) you can see individual expressions, distinguishing features—but that’s rare indeed in photos that follow this trope. (Perhaps less so for paintings, and we’ll come back to that in a moment.) When the ship is large, and therefore the photographer has to be further away, even basic details are lost: for example, could you tell without looking closely that almost all the figures in the last of those four photos are children? Details of the vessel itself don’t tell you anything about where it is, either, and only very rough information about when the picture was taken. Ships travel a long way, and have long service lives: the Vlora was built in 1960 and only broken up in 1996. So when you see an image of a boatload of refugees at sea or at a dockside, there’s very little to tell you when or where the image was taken.

All this means that the image of the ‘refugee boat’ is, if anything, even more standardized, even more of a trope, than the image of a group of refugees fleeing on foot over land. Every time you look at a photo of a refugee boat, in a way you’re looking at every other photo of a refugee boat, too—certainly every other one that you’ve seen, and every other one that whoever produced the image has seen. And every time a photojournalist frames an image of one, he or she is in a way taking a picture of all those other pictures too.

Needless to say, it’s impossible for any of these images to tell us much about the enormous variety of different individual stories, individual lives, on a single refugee boat—let alone the range between an Albanian adult on the Vlora in 1991 and a Basque child on the Habana in 1937. The image above was taken in the Mediterranean in 2014. It won the photographer, Massimo Sestini, a World Press Photo award, and in a way it was ahead of its time, seeming to capture the spirit of this summer: that’s why you may have seen it on the Google refugee appeal or, if like me you’re based in Scotland, the new Scotland Welcomes Refugees site. But in another way it could have been taken anywhere, at any time since press photography became a thing. And, like the standardized photographic image of refugees on land, the ‘refugee boat’ picture has roots that go back much deeper than the emergence of photojournalism. Here’s one very influential predecessor:

Jonathan Jones wrote about Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818-19) earlier this summer, explicitly making the connection with the ‘refugee crisis’. The painting was a media sensation in its time, viewed by 40,000 people when it was exhibited at Egyptian Hall in London in 1820. (I learned about it when I read A History of the World in 10½ Chapters by Julian Barnes, twenty-odd years ago; it’s parodied in one of the Asterix books too.) A detailed exploration of the genealogy of the ‘refugee boat’ image would need an art historian, not me, but I’d suggest that this and other paintings of shipwrecks and their survivors, and the long tradition of paintings of Noah’s Ark at sea in the Flood, would be the place to start looking. Here, I’ll just point out once again that a painting can combine individual detail and panoramic sweep more easily than a press photo: Géricault’s painting is a monstrous seven metres by five (!), so the dead and dying figures are pretty much life size, if seen at a short distance.

But they are seen from a short distance, not from the raft itself–which leads to my final point. Even more than images of refugees on land (or of refugee camps), the viewpoint that pictures of refugees at sea adopt is, almost by definition, not that of the refugees. The viewer, like the photographer, is looking at the boat and the refugees from a different and usually safer perspective. The Sestini photograph is a paradigmatic case, taken from an Italian navy helicopter: not so much a bird’s-eye as a God’s-eye view.

I think it’s important to find ways to go beyond this visual trope: it objectifies the ‘refugee boat’ and it objectifies refugees (and I say that without intending to denigrate the photographers or the worthwhile ends to which such photos are often put). These images shape the meaning of ‘refugee’ before we even articulate it in words, and if that means that when we talk about refugees we immediately think of an indistinguishable mass of more or less interchangeable people, there’s a problem. Massimo Sestini seems to recognize this: in the other pictures that form part of the same reportage–here on the Time website–there are photographs of individuals, taken much closer up. But they’re all taken on navy rescue vessels. The refugees have entered the photographer’s world: he hasn’t entered theirs.

For the photographer, then, the challenge is to change their perspective, and to look at things from the refugee’s point of view. (Over a year after he took this award-winning set of photos, Sestini has started trying to locate some of the individuals pictured in the boat, so he may be doing that.) It’s a challenge for editors, too: the choice of the representative image, the one that’s at the top of the story or on the front page of the website, is the one that matters most, whether it’s a news website or a charity appeal.

But the really great challenge to this objectification of the refugee boat will come from refugees themselves. Refugees are more likely now than ever before to have the means of making their own record of their journey, and swiftly making it publicly available. We’ve heard quite a bit, in recent years, about ‘citizen journalists’ using smartphones and social media to create their own record of events. Perhaps we’ll learn to see refugee boats and their passengers differently when the photos we’re looking at are taken from aboard the boat itself, by refugees.

Next post in this series: the image of the refugee camp.

*I’d had this article on my laptop for a while but not got round to reading beyond the first page or two—my friend David Farrier emailed it to me after he’d read my last post, reminding me that I need to go back to it.

One of my very smart students read this post and emailed this response, which I’m posting here by permission. It includes a link to an article on the Tageszeitung website: what looks like a paywall may come up, but it’s just suggesting you subscribe: scroll down and click on ‘weiter zum Artikel’ to get access.

Comment follows:

—

I just read your blog post about the images of people fleeing on boats, which I enjoyed, similar to the previous posts on that topic. I just wanted to share with you one example from a German news outlet and some thoughts on your general take on the images.

Especially the equipment side of the image production seemed interesting to me. That is also why this came immediately to my mind. The German left-liberal newspaper “Die Tageszeitung” (it was founded as a collective business in the 70s in West Berlin, I think) published what you outline as an idea at the end of today’s post, a reportage filmed by the smartphone of a young Syrian man and documents the journey from Damascus to Germany via Greece and the Balkans. The first link leads to the article and the second to the multimedia reportage (it is all in German but especially the actual reportage is quite self-explanatory- or in Arabic in parts at least):

http://www.taz.de/!5015095/

http://taz.pageflow.io/flucht-fb2ba445-5dff-4a58-b36a-d1367535f413#9025

(I hope the link to the films works. If not, try to access it through the article)

As you mention, photographers are also using other perspectives, such as close ups. I had to think of that as well because I paid attention to how the newspapers I am reading are depicting refugees after having read your postings. The German newspaper “Süddeutsche Zeitung” (also a rather liberal newspaper, though not as left as the “Tageszeitung”) pays a lot of (critical) attention to German and European government policies on this issue and gives generous space to initiatives to support refugees in Germany and elsewhere, incl. the views of refugees and people without official immigration status. Thus, not surprisingly, they quite regularly “deviate” from the “common” way of visually depicting refugees you analyse. Other German media outlets, of course, adhere to it much more.

That made me wonder whether it would not be even more enlightening to look at the range of different ways to depict fleeing people, even in “mainstream” media. This would then allow to ask in what circumstances what editors (can) choose which images. In my opinion this would highlight a bit more that these are choices made by actual people, i.e. editors, journalists, readers, etc. That is especially important, I feel, when you highlight the historic continuities, as through the Géricault painting. I don’t think it is the point you want to make that it is a continuity that is unavoidable, but I can imagine it could also be read like this.

However, I guess that could easily expand into a research project, rather than a blog post at the side. Well, thank you in any case for a thought-inspiring blog post.

—

That would make a pretty good research project, I think!

LikeLike