One of the things I’m thinking about for a current book project is how the ground that a refugee camp stands on affects the lives that its residents live there. In autumn 1918, unusually heavy rain turned the beaten-earth tracks of the Baquba refugee camp near Baghdad into deep mud. It was impassable for the ox-carts that delivered rations to the over 40,000 residents of the camp, and for the cars that transported anyone suspected of contagious disease to hospital. Consequences like this often result from the interaction of a camp and its inhabitants, the ground beneath them, and the weather: consider the news reports from modern-day camps like the Calais ‘Jungle’ or Moria on Lesbos. They often trigger or contribute to interventions by the authorities to improve matters, though on the authorities’ terms. At Baquba, a light rail system was installed along the camp’s main thoroughfares. This was not for the residents’ convenience: the British army of occupation in Mesopotamia, which ran the camp, did it for its own purposes of supply and disease control. The degraded and muddy conditions at the Calais ‘Jungle’ a century later, and international media reporting on them, triggered the partial then full clearance of the site by the French state, and its transformation into a nature reserve—measures that had nothing to do with the residents’ welfare.

Camps are sometimes built on sand, and this poses particular problems. The St Luke’s camp at Haifa in British mandate Palestine was one of many across North Africa and the Middle East managed by Allied relief agencies during the 1940s. (The book is about these camps.) It was on the coast, and its tents were pitched on sand: ‘whole camp would be washed away after a heavy rainstorm’, a field report noted. Other camps run by the Middle East Relief and Refugee Administration (MERRA), later absorbed into the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), were built on different sand, desert rather than beach. At Khatatba in Egypt, the sand created harsh conditions for the camp’s children, disproportionate (as is often the case) among a population of Yugoslavs who had fled German occupation: ‘the sand scorches their feet and fills their lungs with dust’. Sick children were sent to the camp at Tolumbat, on the coast near Alexandria, a former army convalescent camp where the air was better and the ground less hostile, though prone to flooding.

The largest of all the MERRA/UNRRA camps, at El Shatt near the Suez canal, was also built on desert sand. It was actually made up of three quite widely separated subcamps connected by a tarmac road and some wire-mesh desert tracks: ‘a good deal of the intra-camp traffic takes off on its own on the desert trying to avoid soft sand, tents, and small Yugoslavs’. The sandy ground was not just a problem for supply trucks. Its tenuous soil ecology lacked the micro-organisms, small creatures, and plants that might break down organic matter. It was ‘sour ground’, having been much pissed on by the residents and the servicemen who preceded them (El Shatt had previously been a rear camp for British and British imperial forces).

Camps built on sand often have sanitation problems. Well into El Shatt’s time hosting refugees, the tents in one of its three subcamps still lacked any floors, which made sanitation ‘inefficient’, as a report noted with some understatement.

It is difficult to instil a feeling for home cleanliness to people who sleep or sit all day long in the sand. Moreover a lot of water is used to wet down the sand, a practice which is perfectly logical to both the refugee who dislikes sand blowing about, and to the fly who in interested in increasing his number.

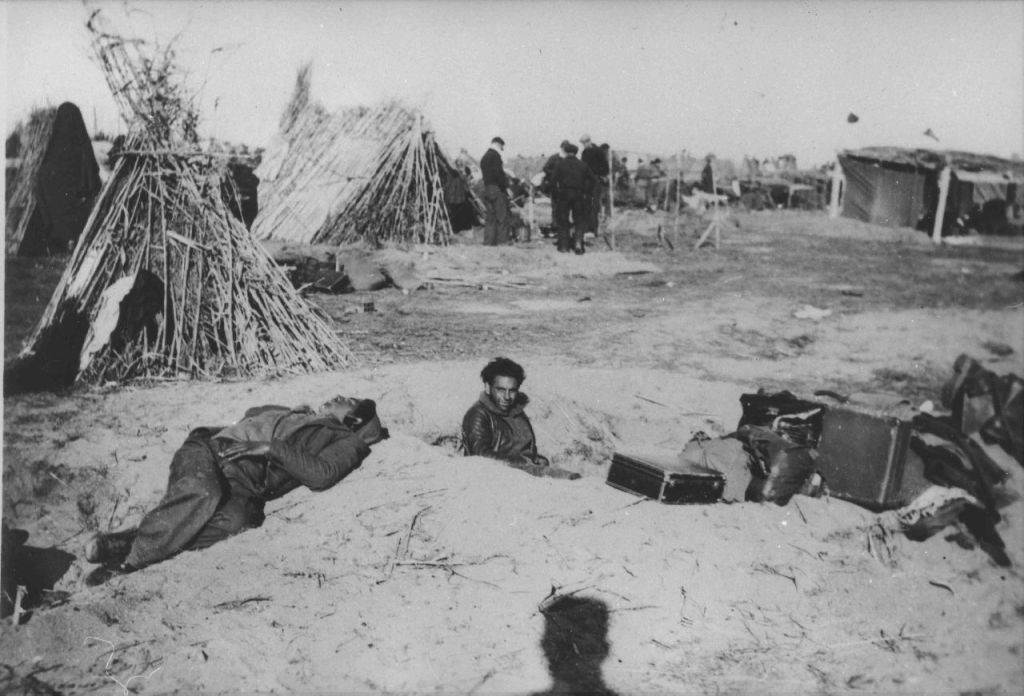

A few years earlier, when several hundred thousand Spanish Republican refugees fled over the Pyrenees into France before the victorious fascist army, the French government disarmed them and sent men of military age to harsh encampments on the beaches of the Roussillon, with little more than barbed wire for shelter. Exposed to the winter weather, they were left very vulnerable. And sanitary conditions were dreadful: they had to wash their clothes in sea water, and it’s hard to dig an effective latrine trench in sand. The Haifa camp, which was intended to care for its residents rather than contain and discipline them, may have stood on sand, but it had chemical toilets.

Gibli, gibli, friends, the children shout.

Where is our Area G?

We can’t see anything

Here it is, here it is, friends, this is what it says.

Mom, dad, friends, where are you?

It will take our tents away. Let’s tighten the ropes!

Gibli, gibli !

But residents of camps have their own experiences of sand, and they aren’t always negative. Dragoslava Williams, née Stojanovic, spent most of her childhood in displacement, leaving Yugoslavia with her family in 1939 at the age of 3 and travelling down the Danube then through Russia and the Caucasus into the Middle East. They reached Egypt in 1945, and went first to the UNRRA camp at El Arish on the Mediterranean coast. Interviewed some sixty years later, she still remembered its ‘beautiful sand’. From there the family went to El Shatt, where they spent three years before emigrating to Australia in 1948. Like other Yugoslavs who lived in El Shatt after the war, they could not return to a Yugoslavia that was now under communist rule: Draga’s father was a royalist. But the Yugoslavs who had lived there in 1944–45, and did go home as the war ended, were highly mobilized in support of the communist Partisans, and self-governed (under British military supervision) by Partisan representatives. Children living in the camp in these years had learned Serbo-Croat from a colourful primer that illustrated the letter G with ‘gibli’ [Arabic qiblī], the name of the south wind heavy with desert sand. The illustration shows two children caught in a sandstorm whose wind threatens to lift the roof off a tent, by a sign marked ‘Area G’. Other Yugoslav children learned from the sand in an even more literal sense: at Tolumbat, pencils, pens, and paper were scarce, and reserved for older children. Younger children learned their letters by shaping them in sand. Josef Radic taught the geography of Dalmatia by making a relief map in sand.

![A line of seven young children squat down in sand. They are not looking at the camera, but at letters moulded into the sand in front of them: NAŠA ŠKOLA [our school]](https://singularthings.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/s-0800-0008-0010-00036.jpg)

Over time, camp residents could begin to transform the soil ecology of the camp. At El Shatt, residents used low sand embankments to demarcate the ‘gardens’ of individual tents. Children kept melon pips and planted them in little raised beds held in by sand or bricks. (These are shown in the photo at the top of the post.) Even in the harshly punitive camp for Spanish Republicans at Argelès-sur-mer in 1939, the sand offered some possibilities to residents. The photo below, taken in February or March of that year by a French garde mobile named Albert Belloc, shows men in the camp resting in holes they had dug out of the sand, to provide at least some shelter for themselves.

How else does the ground beneath a camp affect the lives people live in it? There’s plenty more to think about here.

Acknowledgments

I’m working on this book with Katherine Mackinnon, whose excellent research identified most of the sources here. It builds on the earlier work of Baher Ibrahim, which produced this very useful research guide [PDF] to refugee settlement and encampment in the Middle East and North Africa, 1860s-1940s.

Sources: quotes

Haifa

Untitled survey, ‘Name of camp: Haifa’, compiled 6/8/44 (ie June 8 1944, I think) based on documents produced in 1943. UN Archives, S-1263-0000-0008-00001, quote at p14 of PDF.

Khatatba

‘Second Report on Khatatba Camp for Yugoslav Refugees’. Ida McNare, American Red Cross, Khatatba, to Charles Bailey, director, ARC Middle East Operations, 9 Sept 1944. UN Archives, S-1264-0000-0057-00001, quote at p2 of PDF.

El Shatt

‘Information requested by Refugee Camp Unit Bureau of Areas on El Shatt Camp’, survey response by S.K. Jacobs, n.d. UN Archives, S-1264-0000-0054-00001, quotes respectively on pp31-32 of PDF (pp30–31 of document), p11 of PDF (p9 of document), p13 of PDF (p11 of document).

Sources: images

‘Melons abound in Egypt, and children keep the pips to make gardens grown in front of tents in UNRRA’s biggest refugee camp in the Middle East where there are 20,000 living under canvas.’ Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsa.8d37950/

Početnica 1945 [Spelling book 1945]. UN Archives, S-1449-0000-0120-00001, p32 of PDF (p30 of book).

‘Five year olds learn to write on the sand at Camp Tolumbat’. UN Archives, https://search.archives.un.org/middle-east-five-year-olds-learn-to-write-on-the-sand-at-camp-tolumbat

‘Using sand, teacher Josif Radic of Yugoslavia patiently creates a relief map of Dalmatia for his refugee pupils’. UN Archives, https://search.archives.un.org/middle-east-using-sand-teacher-josif-radic-of-yugoslavia-patiently-creates-a-relief-map-of-dalmatia-for-his-refugee-pupils.

‘Réfugiés se reposant dans leur trou’ [Refugees resting in their holes]. Departmental archives, Pyrénées-orientales, https://archives.cd66.fr/mdr/index.php/docnumViewer/calculHierarchieDocNum/366269/366195:366270:366271:366269/900/1440